Black Phone 2

by Hope Madden

I was cautiously optimistic about director Scott Derrickson’s sequel to his creepy 2021 Joe Hill adaptation, Black Phone. And lo and behold, within the first ten minutes, Black Phone 2 had worked three of my favorite things into its tale: Pink Floyd, Duran Duran, and extreme profanity from children.

I’m listening.

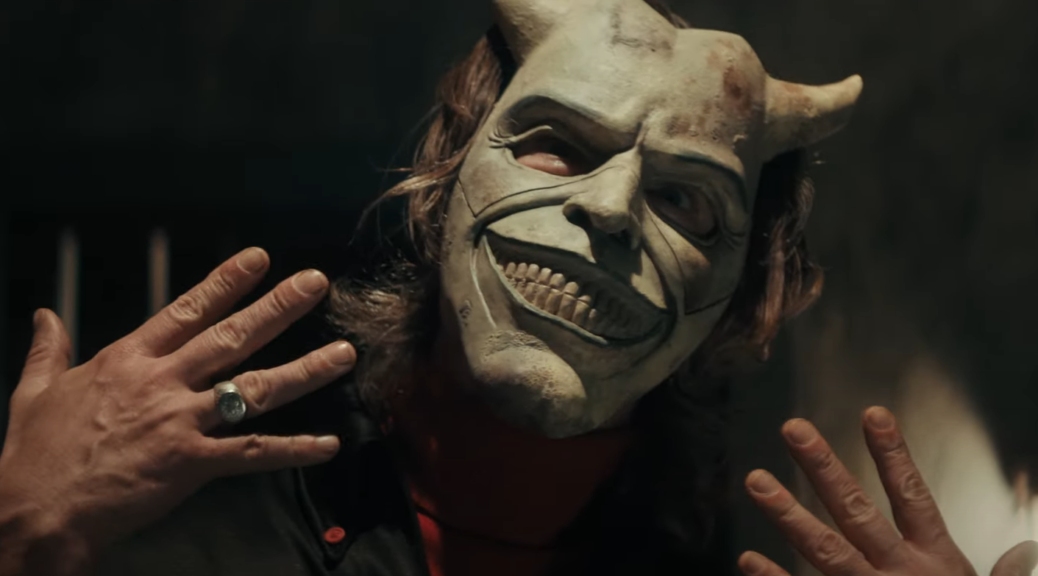

Finney (Mason Thames) and his little sister Gwen (Madeleine McGraw) are struggling to find a new normal after Finney killed serial killer The Grabber (Ethan Hawke) a few years back. What Finn doesn’t want to admit is that he still sees that masked demon in a top hat everywhere he looks. Meanwhile, Gwen’s dreams have taken a decidedly sinister turn.

Last time out, Derrickson, writing with longtime collaborator C. Robert Cargill, filled out Hill’s short story with a just-strong-enough b-story about Gwen and her dreams. It gave the film a larger world to live in and enhanced the supernatural elements of Hill’s original nicely.

For the sequel, Cargill and Derrickson mine Gwen’s abilities for the bulk of the story, as her dreams lead the two siblings to a Christian sleepaway camp called Alpine Lake. Derrickson’s early 80s timeline allows for an analog look that lets him artfully conjure Friday the 13th, of course, as well as A Nightmare on Elm Street (the original and episode 4). There’s even a little Curtains thrown in there. Fun!

The script tries to close too many circles, find too many coincidences, and the story collapses on itself. Worse, a perfectly grotesque and bloody climax is kneecapped by an unfortunately saccharine ending.

Still, there is plenty of bloodshed and gore, and Hawke still cuts an impressive figure in that mask. We don’t see or hear enough of him in a story that feels rushed, but you don’t need much of The Grabber to be creeped out.

My real worry was that if Gwen and crew didn’t figure out what’s what and get home from camp in time, she might miss the Duran Duran show. Talk about tension!