The Fight

by Matt Weiner

No disrespect to taut legal thrillers, but after watching The Fight it’s safe to say nothing will stack up to the real thing during the Trump administration. What began outside a New York court just days after the inauguration in 2017—the night the ACLU scored an early victory against the administration’s first version of what would become the “Muslim ban”—inspired documentary filmmaker Elyse Steinberg (Weiner) to follow the legal organization’s urgent and frequent races against the clock to challenge the administration’s advances on just about every key issue the group defends.

Surprisingly, given the marquee cases the group has been involved in over the years, this is the first time they allowed access inside their offices. Much less surprisingly, that turned out to be a smart move under this administration: the filmmakers (Steinberg, along with co-directors Eli Despres and Josh Kriegman) have no shortage of legal battles to follow.

Steinberg knows how to humanize her subjects. (She made Anthony Weiner almost sympathetic, after all.) The ACLU lawyers followed in the film are big names in their practice area, and recognizable faces to cable news watchers or the kind of person who has a favorite vice president. But it’s the less guarded moments that reveal the full gravity of this work: Dale Ho flubbing the lines in front of a mirror that he’ll later deliver to the Supreme Court, or Brigitte Amiri celebrating a major win with “train wine” on the Northeast Corridor. It’s equal parts grim and joyful.

To both the filmmakers’ and the ACLU’s credit, there’s acknowledgement that the headline wins are tempered by the reality of the American legal system. Even the wins might only be temporary, as the administration endlessly finds ways to retool the laws in ways that pass muster with a sympathetic Supreme Court.

In these moments, the film’s main players seem to tiptoe up to a line of nihilism. But only just up to that line. We hear lawyers sigh that arguing the merits of a case doesn’t always matter in front of the nation’s highest court. And then there’s the criticism from those within the organization itself over their role in Charlottesville, and what free speech and democracy look like in this era.

Ultimately though, this cri de coeur isn’t looking to dismantle the entire system… yet. (Let’s see how disheveled they look if there’s another four years of this.) The film’s subjects refuse to jettison small-d democratic values, or a belief in the foundation on which these laws are built. It’s inspiring, in the way that Charlie Brown thinking he’s going to get that football this time is also a testament to the human spirit or something.

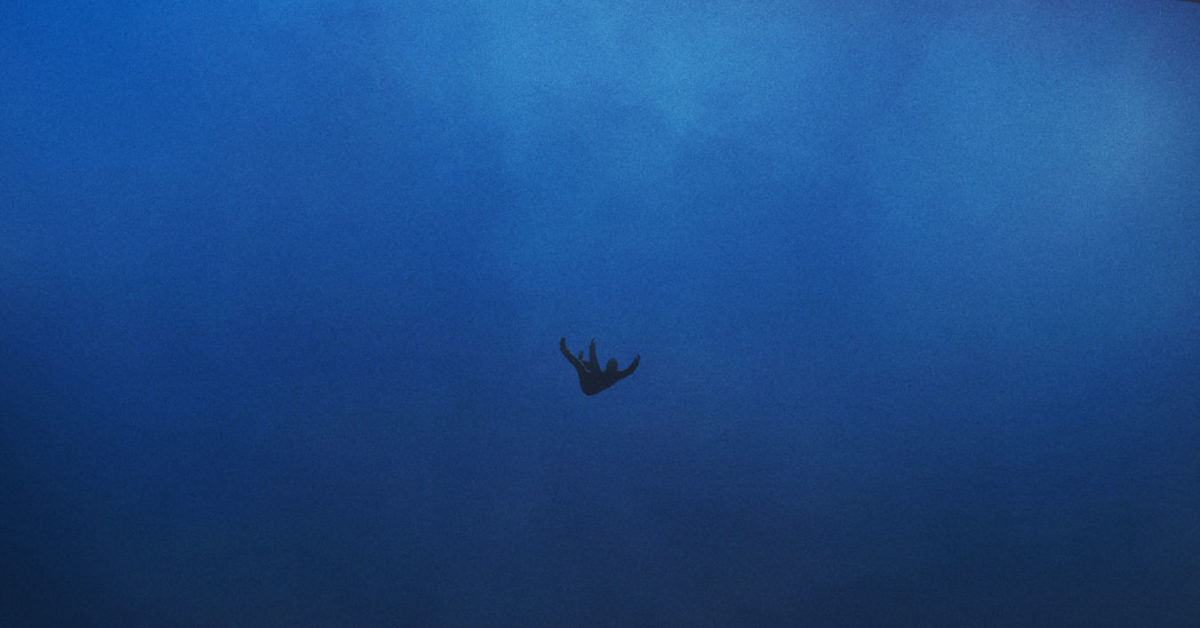

The filmmakers are aware of this contradiction too, though. It’s why the most powerful moments don’t take place in august courtrooms like the generic biopics these cases are bound to spawn some day. Instead, it’s with the individual people at the heart of the cases—the lawyers, eschewing private practice to go from airport to airport forever in search of a phone charger, but especially the anonymous people who found themselves in life or death situations with their fate hanging on the decision of a handful of judges.

For one of these cases, “Ms. L” v. ICE, the camera crew is present when the asylum-seeking mother reunites with her daughter after being separated by the government. She sheds tears of joy, but also lets out a shocking, endless wail. These cases might have good endings, but not happy ones.