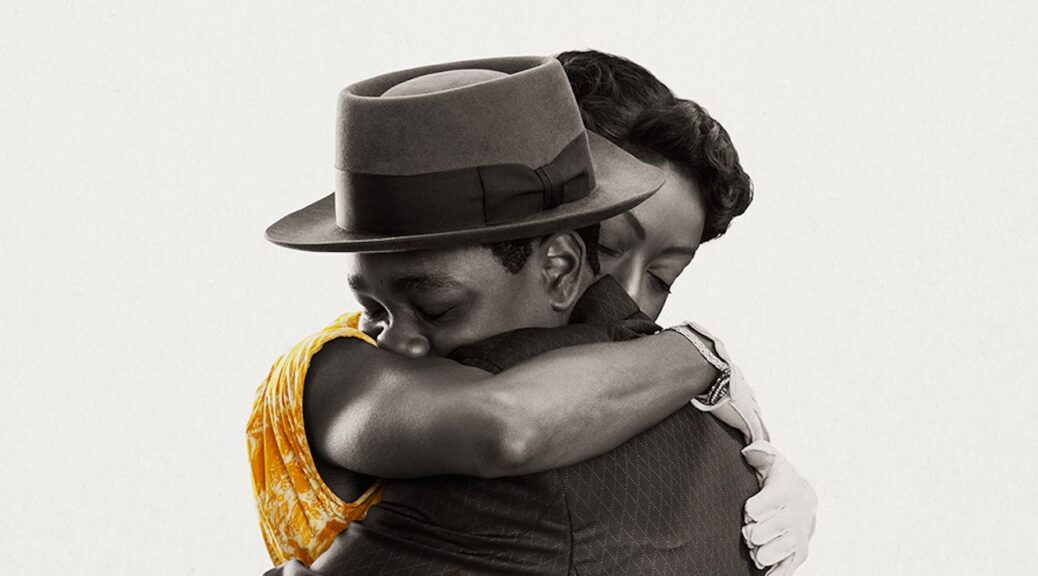

Till

by Hope Madden and George Wolf

Get to know Danielle Deadwyler.

Last year she stole scenes in the super-star-studded Western spectacle The Harder They Fall. In 2019, she seared through the screen in Lane and Ruckus Skye’s woefully underseen (See it! Do it!) Devil to Pay. And now she carries the weight of the world with grace as Mamie Till-Mobley in Chinonye Chukwu’s remarkable Till.

Deadwyler is hypnotic, a formidable presence as a woman who endures the unendurable and then alters history.

And Chukwu wastes no time making this history come alive.

For decades, we’ve mostly been shown the same faded, B&W snapshot of Emmett Till. Chukwu, as director and co-writer, bathes us in color and warmth from the opening minutes.

Mamie and her teenage son Emmett aka “Bo” (Jalyn Hall, charming and heartbreaking) share loving and tender moments as he prepares to leave Chicago and visit family in Mississippi. Deadwyler delivers Mamie’s apprehension with tense stoicism, and her eventual grief with gut-wrenching waves of pain.

Chukwu’s overall approach to the period piece offers hits and misses. The vibrant palette brings urgency to the past while fluid camerawork puts you in the parlors, courtrooms, streets and churches, making you part of the history you’re watching. It’s a beautiful film.

At the same time, much of the plotting, score and script fall back on tropes of the period drama. This comes as a particular disappointment given the filmmaker’s fresh and resonant approach to her 2019 drama, Clemency.

And yet, Chukwu mines these familiar beats for organic moments that create bridges to today. Victim blaming, character assassination, trial acquittals and the intimate helplessness of systemic oppression are all integral parts of this story, and ours. Those are ugly truths, but Till never loses its sense of beauty. There’s a remarkable grace to the film, even as it is reminding us that this American history is far from ancient.

There’s no denying Deadwyler, whose aching, breathtaking turn is certain to be remembered this awards season. In her hands, Mamie’s hesitant move to activism is genuine and inspiring, but it is always grounded in loss.

That loss is the soul of Till, a film that paints history with intelligence and anger as it honors one mother’s grief-stricken journey of commitment.