Men

by Hope Madden

Alex Garland bats 1.000 with his third feature, Men, a terrifying look at the complicated aftermath of trauma.

Jessie Buckley (flawless, as always) plays Harper, a woman in need of some time alone. She rents a gorgeous English manor from proper country gentleman Geoffrey (Rory Kinnear) and plans to recuperate from, well, a lot.

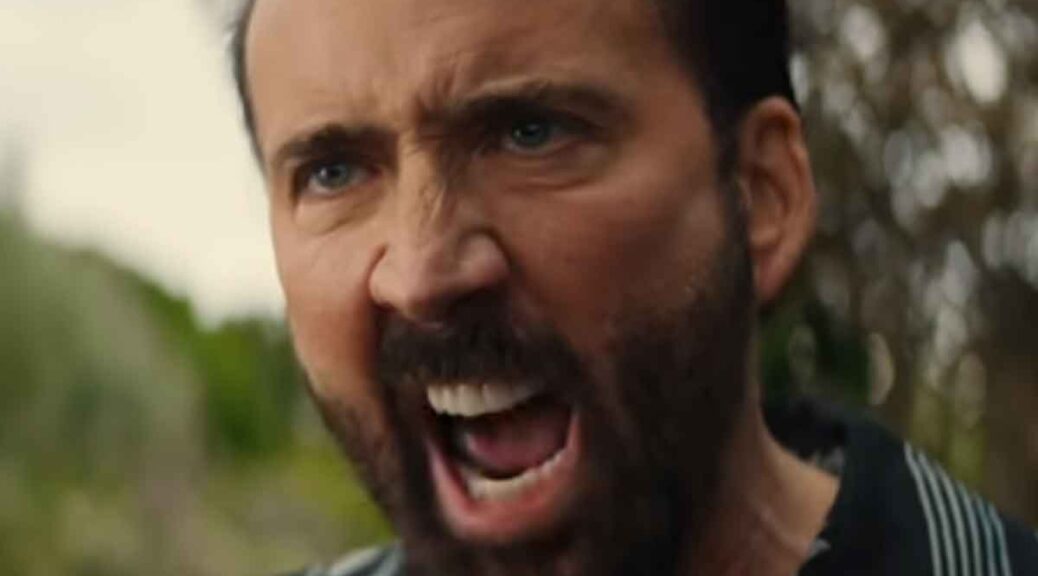

Garland unveils Harper’s backstory little by little, each time slightly altering our perception of the film. The more about Harper we learn, the more village folk we meet: vicar, surly teen, pub owner, police officer, and a naked man in the woods. Each is played by Kinnear—or by actors sporting Kinnear’s CGI face—although Harper never mentions this, or even seems to notice.

Is she seeing what we’re seeing?

All is left open to interpretation. An easy read, given Kinnear’s multiple roles, is simply that all men are the same. And while each of Kinnear’s characters represents a specific and common type of male threat, as bizarre reality begins tipping further into outright fantasy, it seems likelier we are seeing more of Harper than we are of men in general. She is putting a face—the same face—on a lifetime of traumas, large and small.

Garland’s bold visuals—so precise in Ex Machina, so surreal in Annihilation—create a sumptuous environment just bordering on overripe. The verdant greens and audacious reds cast a spell perfectly suited to the biblical and primal symbolism littering the picture.

Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow’s score meshes with Garland’s lush imagery, releasing a blend of music, ambient sound and, at its most eerily beautiful moments, Buckley’s voice. The result is powerful and unnerving.

Men is more of a head-scratcher than either of Garland’s previous films. Yes, even Annihilation. It’s far more of a horror film, for one thing, and far less of a clearly articulated narrative. Rather than clarifying or summing up, the film’s ending offers more questions than answers. But if you can make peace with ambiguity, Men is a film you will not likely forget.