Sweet Girl

by George Wolf

You know that feeling when someone comes out of a security door at the precise moment you’re trying to come in without a key?

Or when a major cable news show puts your call right through to the air on the very same day you find a uniform in exactly your size hanging up and waiting for you to blend in somewhere you don’t really work?

Me neither. So while Netflix’s Sweet Girl calls attention to a very real problem in America, the narrative that drives it trades authenticity for gimmicky contrivanace.

Through a frequently changing timeline we meet Ray Cooper (Jason Momoa) and his daughter Rachel (Isabela Merced). Tragedy hits their Pittsburgh-based family when wife/mother Amanda Cooper’s life is cut short by cancer. Amanda fights hard, but finally succumbs when a promising new drug is withheld by obnoxious Pharma Bro Simon Keely (Justin Bartha).

While Keely and Congresswoman Diana Morgan (Amy Brenneman) are on live TV debating prescription drug prices, Ray calls in to blame the price-gouging Keely for his wife’s death, and to promise violent revenge.

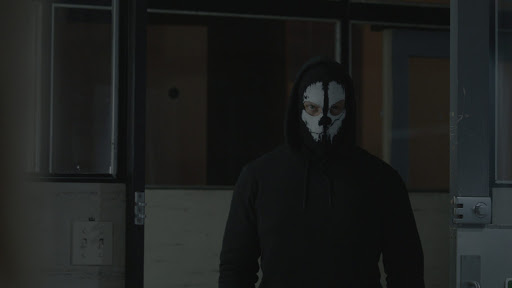

Ray’s nationwide threat seems to only arouse the interest of an investigative reporter on the trail of a Big Pharma conspiracy, and when Ray’s meeting with the writer turns unexpectedly bloody, father and daughter become fugitives hunted by both the cops and the killers.

In his feature debut, director Brian Andrew Mendoza utilizes Momoa’s hulking charisma via some standard fight choreography, but the gifted Merced seems wasted. Writers Gregg Hurwitz (The Book of Henry) and Phillip Eisner (Event Horizon) serve up a journey of convenience on the way to a third act twist that will define how smoothly the film goes down.

If you can keep your eyes from rolling, this film may feel like the franchise kickstart it aims to be. Otherwise, Sweet Girl leaves a pretty sour aftertaste.