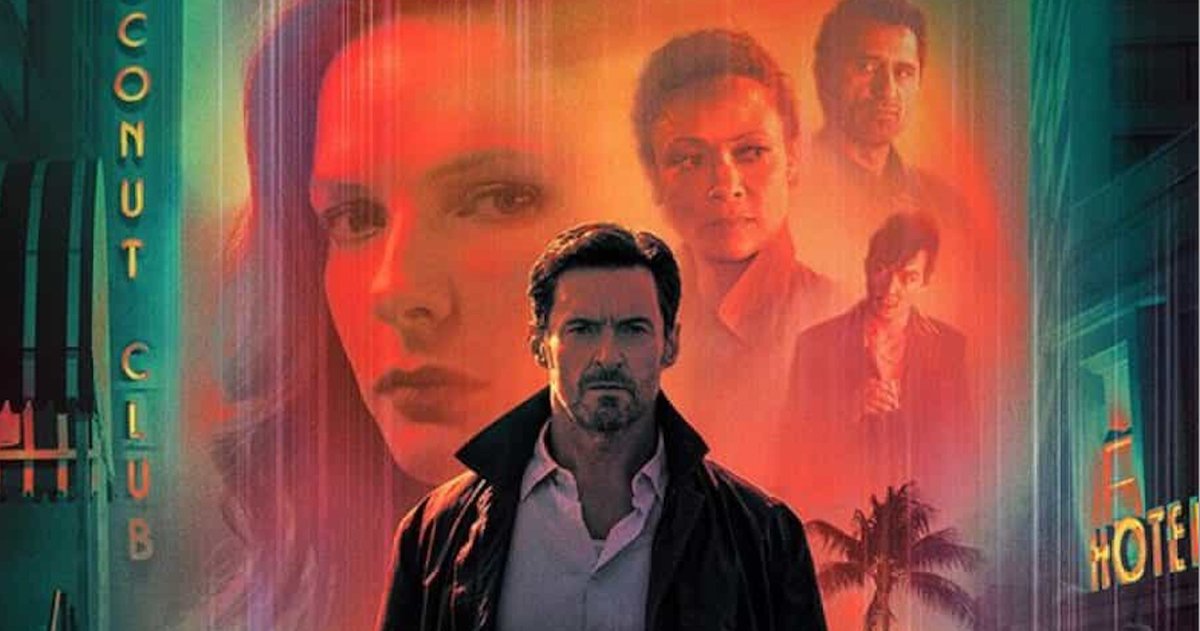

No Man of God

by Hope Madden

True crime is quite a phenomenon, isn’t it? It’s been a staple of watch-at-your-own-risk entertainment for generations, but podcasts have set a genre fire that seems unquenchable. Filmmakers have taken notice.

Still, do we need more Ted Bundy? Joe Berlinger made a miniseries (2019’s Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes) and a feature (Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, also 2019). Then there was 2020’s miniseries Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer, which, like Extremely Wicked, told the Bundy tale with the voice of a former girlfriend. And in a few weeks, Daniel Farrands kicks off his American Boogeyman serial killer film series with a feature on Bundy.

Is it even possible for filmmaker Amber Sealy to tell us anything fresh? And even if she could, is there any legitimate reason to continue to rehash the behavior of such human garbage?

Working from a script by Kit Lesser, Sealy attempts to demystify Bundy, focusing not on his crime spree at all, but on his final years on death row. No Man of God spends most of its time in a confined, colorless chamber where Bundy (Luke Kirby) and FBI profiler Bill Hagmaier (Elijah Wood) converse.

Both actors deliver nuanced, unnerving performances. Their interplay and the evolving relationship help Sealy overcome the limited action, institutional color palette, and dialog-heavy run time.

Hagmaier is essentially the vehicle for the audience. Why is he spending his time with this heinous being? He just wants to understand.

That’s our excuse too, right? And that’s also the danger — at least it is in every movie ever made concerning an FBI profiler trying to get into the head of a serial killer, and No Man of God is no different. Is good guy Bill really Bundy’s opposite, or is he capable of the same acts of violence against women?

There are flashes in Sealy’s film where she nearly punctures her rote though well-acted tale with genuine insight about misogyny. But the film is never as interested in the women harmed by Bundy’s narcissism, insecurity and psychosis as it is in those traits he bore.