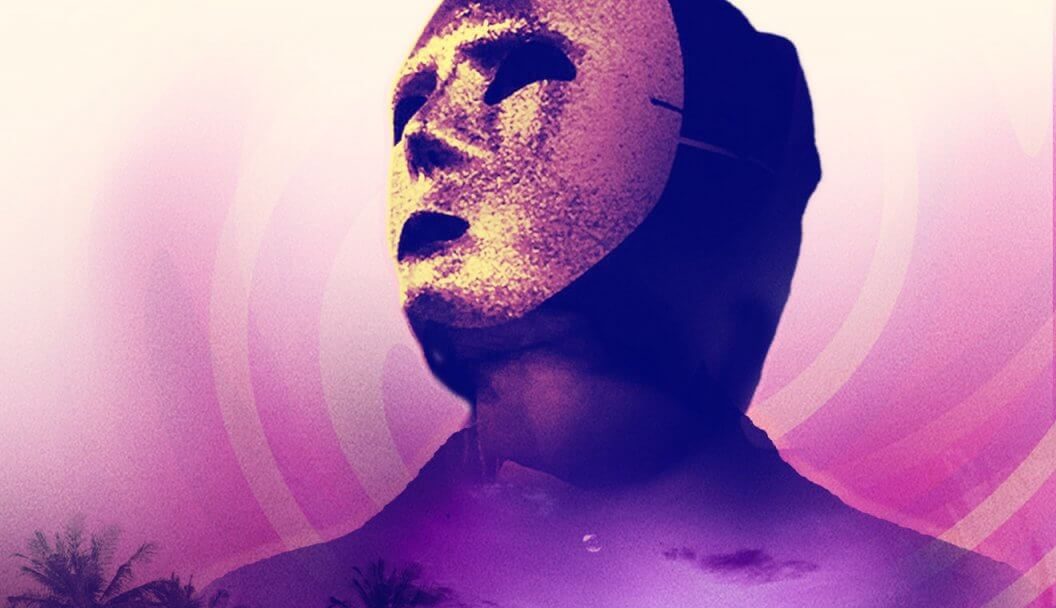

Teddy

by Hope Madden

Even a man who is pure in heart

And says his prayers by night

May become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms

And the autumn moon is bright

Teddy (an exceptional Anthony Bajon) may not be all that pure in heart, but he’s not such a bad kid. What he is, is a loser. He knows it. “We’re the village idiots,” he tells the uncle he lives with.

Teddy’s an outsider in his very small French hamlet, a ne’er-do-well who seems harmless enough. He has a job —one he hates. And he has a girlfriend, Rebecca (Christine Gautier) — but how long can that last? Her family can’t stand him, and she’ll graduate at the end of the term. Then what?

Before we can find out, Teddy’s bitten by something in the woods. Suddenly, by the light of the moon (which seems to forever coincide with some kind of angry humiliation Teddy faces), he loses consciousness and then wakes up naked and covered in blood.

Writers/directors/brothers Ludovic and Zoran Boukhera tap into classic monster movie mythology (and sometimes score, with fun results) to mine lycanthrope lore for metaphorical purposes.

Which is usually what werewolves are used for in movies, including the 1941 classic that spawned that poem. Anyone can be cursed, it seems, and under the right circumstances, anyone can become a monster.

In this case, Teddy represents the marginalized, angry white male. The havoc he wreaks? Well, it’s not hard to figure out what that represents. Truth be told, Teddy is almost off-putting in its empathy for the aggrieved male so disillusioned by disappointments and limitations that he becomes monstrous.

I suppose that makes Teddy feel a bit transgressive, but the reason it works is Bajon’s amiably brutish performance. A horror film is rarely worth its weight in carnage if it can’t engender some empathy, provoke some tragedy. Thanks to Bajon and a strong ensemble around him, the film makes you feel something for an enemy you might rather just hate.

It’s not often you get an official Cannes selection on Shudder. I guess that’s one more reason to watch Teddy.