Monthly Archives: October 2025

Windflower

Anemone

by Hope Madden

As a young filmmaker, would having arguably the most revered actor of his generation—perhaps of all time—as a father be a blessing or a curse? For Ronan Day-Lewis, directing his first feature with co-writer and lead actor (and dad) Daniel Day-Lewis, it seems to be working out.

Anemone is a tale of fathers and sons, of one generation of men inflicting damage upon the next, and the tenderness that either dies, finds an outlet, or runs to madness.

Sean Bean a is Jem, a good man who strikes out from his dodgy neighborhood in Northern England to the woods, led by the navigational coordinates on the back of a page that reads: Anemone: In Case of Emergency, Break Glass.

The coordinates lead him to his brother, Ray (DDL), a hermit since his time fighting against the IRA. Ray is wanted at home.

Like many of Day-Lewis’s greatest performances, his work here impresses with lengthy stretches of silence punctuated by a couple of brilliantly executed monologues. His lean and scrappy physicality belie the character’s vulnerability in ways that expertly match Ray’s reticent then vulgar speech.

Ray’s a man off the rails, while Bean deftly crafts a character who’s found comfort and strength in structure. Neither actor overplays the brothers’ differences, rather falling into a tenuous if lived-in familiarity.

The great Samantha Morton and an impressive Samuel Bottomley round out the cast, but as usual, all eyes are on Day-Lewis.

RDL knows it, not only providing memorable lines, but crafting an atmosphere that evokes Ray’s troubling inner landscape. Bobby Krlic’s (Eddington, Beau Is Afraid, Midsommar) score conjures an angry melancholy while moments of painterly surrealism deliver flashes of beautiful, hopeful madness. Even when lensing the natural elegance of Ray’s isolated world, RDL and cinematographer Ben Fordesman (Love Lies Bleeding, Saint Maud) evoke a magical splendor.

Anemone feels uncertain of how to resolve itself, to bridge the two worlds it creates. Structure failed Ray, and it nearly fails Anemone. But the film offers more than enough reason to believe in filmmaker Ronan Day-Lewis. And if you needed another reason to believe in actor Daniel Day-Lewis, well, here you go.

Tall Tales and Fiction

Killing Faith

by Hope Madden

A raucous opening sequence eventually settles into a classic old Western vibe that keeps you guessing in Ned Crowley’s latest, Killing Faith.

Like Mary Bee Cuddy in The Homesman and Joanna in News of the World, Sarah (DeWanda Wise) is in need of a traveling companion. Her daughter (Emily Ford) needs help that the town doctor (Guy Pearce) can’t offer. Not that the ether-sniffing doc has been much help to his patients of late.

Dr. Steelbender is an ether addict on account of a plague of sorts. Voiceover tells us of a sickness ravaging the countryside almost as savagely as a notorious group of bounty hunters. But Sarah is determined to take her daughter to see Dr. Ross (Bill Pullman) because he deals not just in medicine, but in holy healing.

Crowley’s shot making, particularly in the opening act, is equal parts stunning and unnerving. At his best, he tells the tale like a picture book, images sharing as much of the story as dialog. There’s a grim poetry to the shots that creates an beautifully brutal atmosphere as it delivers information.

Pearce has made a lot of movies, many of them horrible, most mediocre, but he does have a pretty good track record with Westerns. John Hillcoat’s The Proposition is one of the most affecting Westerns of the 21st century. Killing Faith doesn’t nearly reach that high water mark, but it has its moments.

I like the more contemporary Westerns, where no one’s to be trusted and everyone’s a weirdo. Killing Faith is at its most compelling when our little band of travelers finds themselves among unexplained carnage or unexplainable fellow wayfarers. Joanna Cassidy is especially delightful in a macabre way.

But a couple of obvious turns and the general simplicity of the story keep Killing Faith from reaching classic status.

The film loses steam whenever it clings too tightly to its main themes, its hero’s journey. But Crowley elevates that well-worn road with ideas of being haunted by the sight of innocence corrupted, something that connects the Western with dystopian tales, like John Hillcoat’s other Pearce-starring fable, The Road.

All Westerns are about redemption. The best Westerns, new or old, are about hope. Can you allow yourself a flicker of hope? The answer is often what differentiates the classic Western from the contemporary one. Killing Faith toys with those mighty big struggles, sometimes provocatively. The solutions aren’t as interesting as the journey, though.

Poison Pen

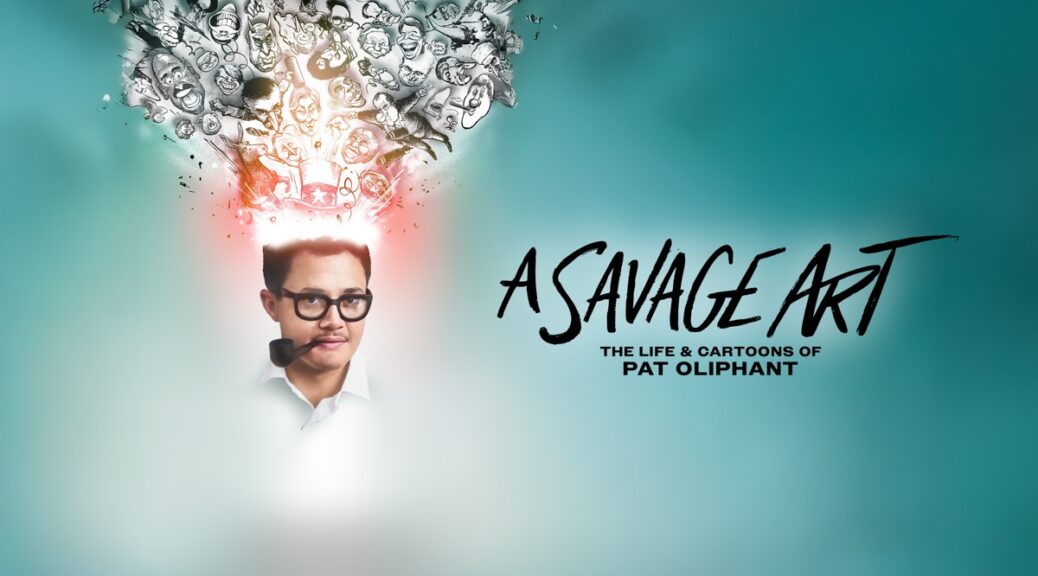

A Savage Art: The Life & Cartoons of Pat Oliphant

by George Wolf

“If Pat Oliphant couldn’t draw, he’d be an assassin.”

That quote gets your attention, even if you don’t know the name Pat Oliphant. Either way, you’ve probably seen some of his work, and A Savage Art: The Life & Cartoons of Pat Oliphant is a broadly effective intro to a legend of political cartooning.

Oliphant wielded a revolutionary artistic style and the kind of cynical mind that had him rebelling against the very committee that awarded him the Pulitzer Prize in 1967. Aided by his alter ego “Punk” the Penguin, Oliphant skewered the political landscape through five decades and ten U.S. Presidents.

In his feature debut, director Bill Banowsky keeps things pretty standard, rolling out a succession of Oliphant’s best cartoons, and chatting with family members and colleagues to provide some personal details that Oliphant himself seems averse to.

And though today’s political and social climate carries some issues that are very relevant to Oliphant’s legacy, Banowsky doesn’t dig in. We do get mentions of the increased threats to a free press, and to the rise of internet memes as a shallow imitation of cartoon commentary, but those seem to be conversations for another day.

Banowsky’s aim is to give a legend his due and maybe spur some interest in learning more. A Savage Art hits that target square.

Slippery

The Ice Tower

by George Wolf

Fifteen-year-old Jeanne doesn’t want to build a snowman. What she wants is an escape, but finds plenty more than she expected in The Ice Tower, Lucile Emina Hadzihalilovic’s dreamlike re-imaging of “The Snow Queen.”

In 1970s France, Jeanne (a wonderful feature debut for Clara Pacini) is among the oldest children in a foster home, where she comforts the younger ones and silently longs for a better life. She finally leaves one evening, taking refuge in an empty warehouse to sleep.

But in the morning, Jeanne finds the warehouse is home to a movie crew, with director Dino (Gaspar Noé, Hadzihalilovic’s husband) filming a new adaptation of the Hans Christian Anderson classic. Mistaken for an extra, Jeanne becomes part of the production and is instantly captivated by the star of the show, Christina (Marion Cotillard).

The Oscar-winning Cotillard is, of course, perfect as the detached and demanding diva who begins to take an equally strong interest in the young Jeanne. But to what end? Hadzihalilovic explores that question with a cold, barren beauty. The aesthetic is tactile and intoxicating, a perfect playground to envelope the film in strange fascination.

The Ice Tower casts an undeniable spell. Despite lingering a bit too long in some dry spots, it crafts an enriching trip to the darker floors of a fairy tale.

No Wake Zone

Bone Lake

by George Wolf

Not long after we meet Sage and Diego, they’re talking about his idea for a novel, debating about what qualifies as “gratuitous” and lamenting that cancel culture has neutered artistic expression.

Okay, intriguing. And then you remember that one poster for Bone Lake features the strategically large “R” rating positioned right after the first word in the title.

Alrighty, then, we’re gonna push some limits with both blood and lust, are we? Have some devilish fun with hot button topics and take no prisoners?

No, we are not. We’re going to play it safe and predictable, borrow heavily from better projects and hope some late stage blood splatter stops the questions about why that poster doesn’t read BonePG-13 Lake.

Sage (Maddie Hasson) and Diego (Marco Pigossi) have booked an incredible lakeside mansion for the weekend. Diego’s even brought a ring along to pop the question, but there are two very big complications. Will (Alex Roe) and Cin (Andra Nechita) have also booked the mansion for the weekend! What are four good-lookings gonna do except share the space and really get to know each other?

The character development is rushed but adequate. Will and Cin are openly sexy free spirits, Diego is more buttoned-up and Sage seems to be settling for the comfy life while missing some walks on the wild side. But more than anything, Diego and Sage both seem like a couple of first class idiots.

Writer Joshua Friedlander and director Mercedes Bryce Morgan want to sprinkle some White Lotus sensibilities over a mashup of Funny Games and A Perfect Getaway. But the inspirations are painfully evident, the revelations overly telegraphed, the internal logic gets shaky and the frolicking more silly than sexy.

None of it goes anywhere worth caring about. The marketing angle, an attention-getting prologue and that early art debate make some promises that are never kept, and this trip to the lake is more bore than bone.