Dreamcatcher

by Brandon Thomas

The music world and the horror world have a simpatico relationship. The Rocky Horror Picture Show and The Phantom of the Paradise are quintessential cool horror rock operas. More recently, Deathgasm – the New Zealand love letter to metal – has gained momentum as a cult classic with its fun mix of gory carnage and shredding guitars.

Where does the world of underground DJing fit into this legacy? Well, if Dreamcatcher is any indication, any legacy might be over before it starts.

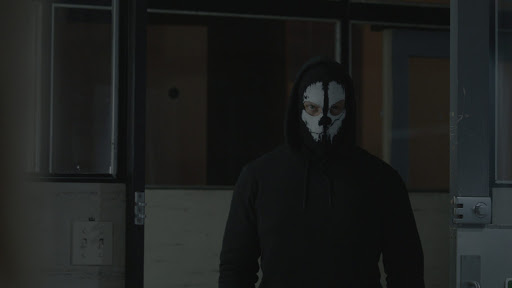

Pierce (Niki Koss) and her friend, Jake (Zachary Gordon), tag along to a hot-ticket underground music fest with Pierce’s sister, Ivy (Elizabeth Posey), and her friend, Brecken (Emrhys Cooper). As the show winds down, tragedy strikes and the friends are thrust into a world of deceit and violence.

It’s hard to get excited about slasher flicks these days. Heck, it was hard to get excited about them by the mid-80s. These are movies built on tropes – it’s what the fans expect – and Dreamcatcher is no exception, despite a few clumsy attempts to be something different. The film swings big, trying to be more character-focused. This approach does nothing but put a spotlight on the incredibly weak script, and pad the running time to an excruciating hour and 48 minutes.

The parts of the movie that are your standard stalk-and-slash clash with the other side that wants to be something more akin to a 90s thriller (think Kiss the Girls or other Silence of the Lambs wannabes). Director Jacob Johnston handles the slasher elements well. These scenes are shot in a more grounded and brutal fashion. When the story starts to dip its toe into character motivation or anything resembling drama, the suspense falls apart.

The characters in Dreamcatcher run the gamut from unlikeable to downright loathsome. Scene after scene of Pierce, Jake, and Ivy airing their petty grievances wear out fast. Dreamcatcher lacks even one character for the audience to latch onto as a surrogate. This ends up making the horror shallow and meaningless.

Dreamcatcher might satisfy die hard fans of the slasher genre, but those looking for something a little more challenging will find themselves checking their watches on more than a few occasions.