by Hope Madden

When I was a kid watching the Oscars, I remember always being perplexed by short film categories. How do people manage to see these shorts?

Good news, kids, it’s gotten much easier. Not only to we now have ShortsTV, but in the last several years, all the nominated shorts have been packaged by category for theatrical showings. And in the cases where the combined run times don’t reach feature length, some bonus shorts are added to the programs.

In this year’s Animation group, don’t look for a lot of silly fun. Or any, really. These animators have beautiful heartbreak in store for you. (Did Pixar not make a movie this year? Seriously, have your Kleenex handy.)

Our Uniform 7 Mins. Director: Yegane Moghaddam Iran

The lightest of the films in the category, Our Uniform delivers a tactile journey through the weight, feel and even sound of the fabric of our lives. Told from the perspective of an Iranian school girl, the film unfolds as a nonchalant conversation about the clothing she wears and how it changes depending on her age and where she is.

The animation is a delight of fabric and flow, and the story releases a sense of freedom and what that feels like.

Letter to a Pig 17 Mins. Director: Tal Kantor Israel

This haunting story, told mostly in black and white with startling uses of pink, follows the dream a school girl has as a Holocaust survivor visits her classroom to tell of a pig that saved his live.

Tal Kantor, who writes and directs, takes unexpected turns in tone. What at first feels like a heartbreaking but beautiful story of survival meeting the apathy of middle schoolers, turns to bitterness and hatred, which turns on its head as it’s translated into the dream of a child. It’s a harrowing, somber but beautiful work.

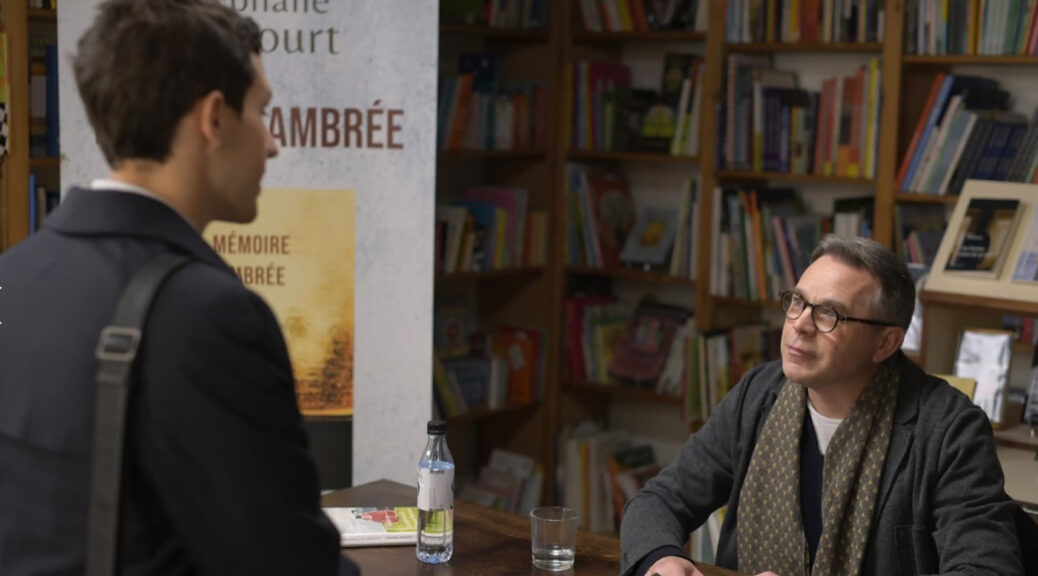

Pachyderme 11 Mins. Director: Stéphanie Clément France

This heartbreaking tale that sneaks up on you is told in lovely, fluid watercolor style animation with a lilting, melancholy delivery as a grown woman looks back at her visits to her grandparents when she was a child.

Together director Stéphanie Clément and writer Marc Rius tease one story from another, the combined tale told with the resigned distance of age by the narrator. The result is touching and lovely.

Ninety-Five Senses 13 Mins. Director: Jared Hess, Jerusha Hess USA

This is not a film I would expect from Napoleon Dynamite director Jared Hess (working alongside his wife and directing partner, Jerusha Hess).

Tim Blake Nelson voices the protagonist of this story, an older man running through a personal tale depicting each of his senses. The delivery is cantankerous and the often quirky animation style suggests homespun wisdom. But the story the Hesses tell consistently surprises. It’s a startlingly human story of redemption, of sorts, and it pulls more tears than the others. (And that is a feat—these movies are out to destroy you!)

War Is Over! Inspired by the Music of John and Yoko 11 Mins. Director: Dave Mullins USA

A carrier pigeon flies through the winter sky, bombs bursting around him. A soldier clomps through snow, his boot print showing the blood beneath the snow.

A chess match unfolds that offers a birds-eye view of the idiocy of war. It’s another tear jerker, but what’s wrong with a good cry?