Daliland

by George Wolf

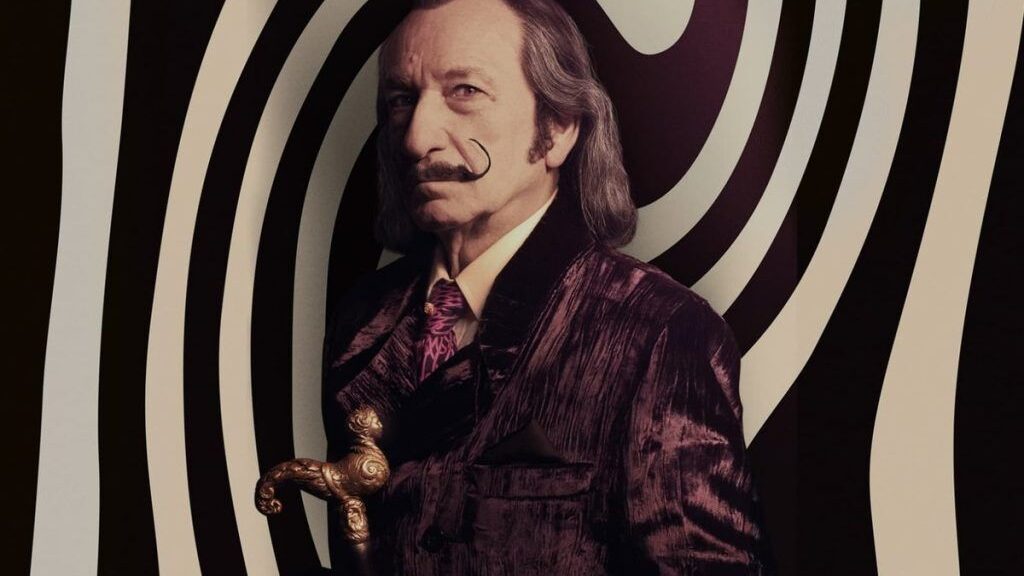

Sir Ben Kingsley as Salvador Dali? That is perfect casting, and an offer that would be hard to resist even if the rest of Daliland was an uninspired bore.

It’s not, although it could use a bit more of the legendary surrealist’s zest for the unconventional.

Director Mary Harron and writer John Walsh (married since 1998) anchor the film in 1974, when Dali’s outlandish antics, eclectic entourage and wild parties (“I need four dwarves and a suit of armor”) have caused the art critics to lose interest in him.

But such a lifestyle costs money.

As Dali’s longtime wife and muse Gala (Barbara Sukowa) presses his gallery for cash, the curator’s young assistant James Linton (Christopher Briney from TV’s The Summer I Turned Pretty) is tasked with “spying” on the master. Dali’s big show opens in 3 days, and the gallery wants to make sure they will have plenty of new works to unveil.

Using a young neophyte as an audience’s window into an icon’s world is a fairly standard narrative device, but Harron and Walsh make sure this world is a fascinating one. Kingsley is as delightful as you expect, Sukowa digs deep into the persona of an aging beauty clinging desperately to power and sex appeal, and Briney makes for the perfect wide-eyed fan on a spiral toward disillusion.

Some of Dali’s more famous friends (Alice Cooper, Jeff Fenholdt, Amada Lear) are represented, creating a Warhol-esque community of celebrities and hangers-on that seems disinterested in the demands of tomorrow.

But while Harron does well showcasing the excess and activity, Dali’s actual artwork is MIA, leaving a few well-placed flashbacks to provide anything close to surreal. As we see the younger Dali (Ezra Miller) pursuing the then-married Gala (Avital Love) and receiving inspiration for what will be his signature style, Kinglsey’s Dali watches with us, inviting us into the conversation. These are not only compelling moments, they are the times when the film seems most in step with the legend that drives it.

It may be young James that carries the film’s biggest arc, but it is the orbit around planet Dali that changes him. Harron and Walsh seem too content to merely document that world on the way to a larger comment on disposable fame, crass classism, and the simple fear of death.

As the title would suggest, don’t come to Daliland for a psychological profile of a legend. Come for a peek inside his carefully curated shelter from the real world, and for the e-ticket ride performance from Kingsley.