Dear Santa

by Rachel Willis

Director Dana Nachman’s feature documentary, Dear Santa, is delightful.

Highlighting the 100-year-old United States Postal Service program, Operation Santa, the film captures the spirit of the season as ‘adopter elves’ make Christmas special for children and families across the United States.

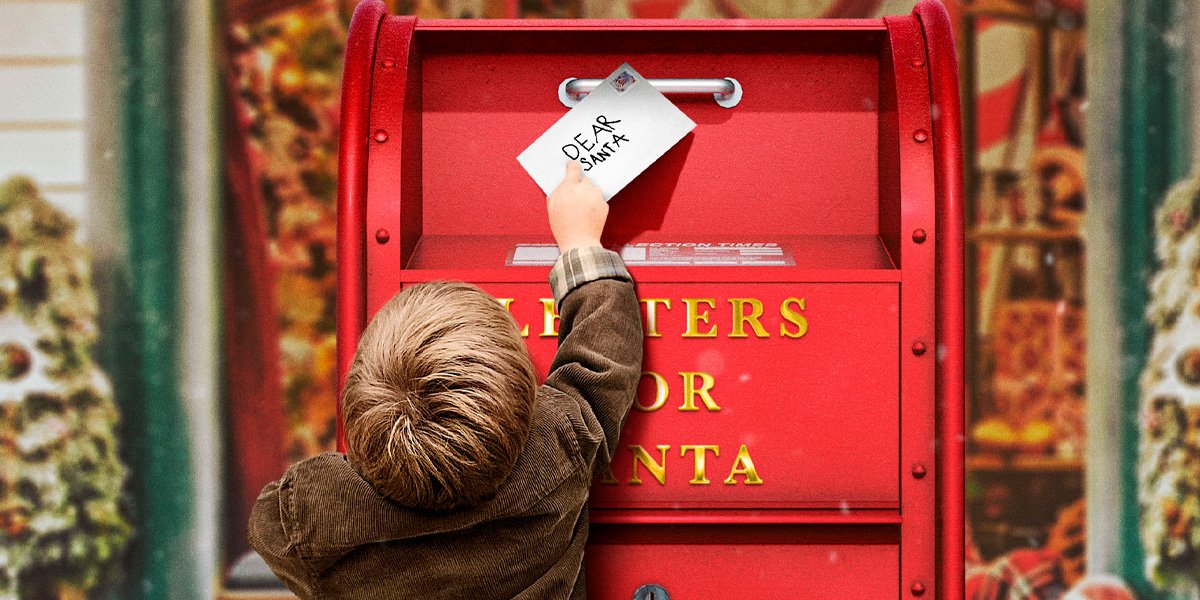

When children post their letters to Santa every year, USPS makes those letters – hundreds of thousands of them – available to the public to ‘adopt.’ This is a chance for individuals, families, schools, and non-profit organizations to read through the letters, select one (or several), and do what they can to fulfill the wishes of the children penning them.

Starting three weeks from Christmas and working forward to the big day, we see how the letters move through the system – starting with the children writing them, to their delivery to the postal service, then on to the adopter elves. Two locations in the US – Chicago and New York – allow the adopters to physically read through the letters, while the rest are available online for those around the country who want to participate.

Nachman (Pick of the Litter) interviews several ‘elves’ in the postal service who work with Santa to read, sort, and deliver the letters received every year. She also follows several adopter elves who help Santa distribute gifts to ‘nice’ children across the country. Then, there are the children themselves, so eager to have their deepest wants and desires met by Santa. One child is particularly keen on receiving a moose for Christmas.

Interspersed throughout is a highlight reel of kids of all ages talking about Santa, who he is, what he does, where he lives, and it’s charming to watch the children explain what makes Santa so special.

This is a family-oriented treat, with the filmmakers and ‘elves’ doing their best to keep the Santa myth alive for any believers. However, older kids who might be starting to question whether the man with the bag is ‘real’, might see through the illusion. Some of those interviewed are more convincing than others when it comes to their work with Santa.

The film is an ode to the United States Postal Service, the hard work they do each year to make Operation Santa a success, as well as to the adopters who make it possible for children to have the merriest of Christmases.

If you’re feeling Grinchy this Christmas, Dear Santa might be just what you need to remember what makes the season so special.