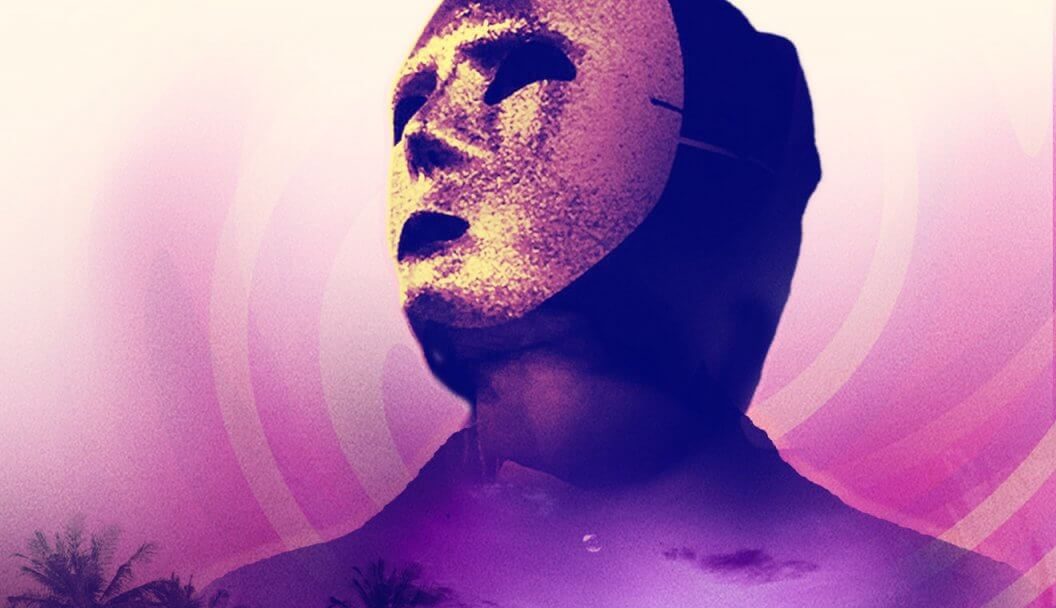

Materna

by Christie Robb

With Materna, director David Gutnik presents four emotional vignettes of women and their relationships with either their mother figures, their children, or both.

While the four women’s stories intersect in a brief, tense moment on a New York subway car, their backstories and how they came to be in that particular car are quite different.

The flashbacks don’t depict simple, saccharine, Hallmark Mother’s Day card relationships. These relationships are layered and complicated—with longing and frustration, the urge to shelter and the urge to smack.

Each of the four lead actresses, Kate Lyn Sheil, Jade Eshete, Lindsay Burdge, and Assol Abdullina, rises to the challenge and convincingly demonstrates the emotional range of her subject. (Eshete and Abdullina also co-wrote the screenplay with Gutnik.)

Rory Culkin shows up to illustrate that the maternal instinct is not solely the purview of those with two X chromosomes.

It’s not a perfect film. The initial segment, while it does pique the viewer’s interest, maybe doesn’t best set the stage for the ones that follow. There are elements that seem to signal sci-fi or body horror that aren’t carried through in the rest of the film. And because of the brevity of each of the vignettes, some of them seem a little roughly sketched, lacking in details that would more solidly ground the perspective of the woman depicted.

At the point of intersection in the subway car, each of the women is keeping herself to herself and adhering to the unspoken etiquette of public transportation. But then a white man starts loudly trying to engage them in conversation that quickly devolves into harassment and violence.

This screaming, egomaniac clearly sees himself as the most important person in the shared space and aims to capture everyone’s attention, making his private life public, doing a kind of emotional manspreading. It’s interesting to contrast this with what the women are dealing with and how their private lives either do or do not impact this public space.

This is Gutnik’s first feature film and I’m looking forward to seeing what’s next.