Chain Reactions

by Hope Madden

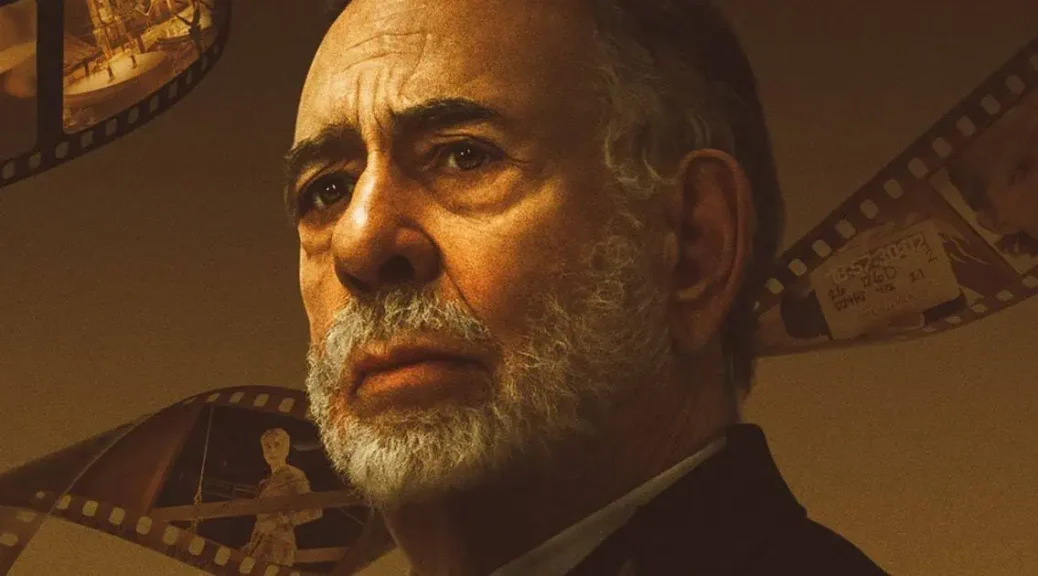

Not everyone believes Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is a masterpiece of American filmmaking. I find those people suspicious. Luckily, those are not the people filmmaker Alexandre O. Philippe (Memory: The Origins of Alien, 78/52) talks to for his latest documentary, Chain Reactions.

The film is a celebration of 50 years of TCM. The celebrants are five of the film’s biggest fans: Patton Oswalt, Takashi Miike, Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, Stephen King, and Karyn Kusama. It’s a good group. Each share intimate and individual reminiscences and theories about the film, its impact on them as artists, and its relevance as a piece of American cinema. What their ruminations have in common is just as fascinating as the ways in which their thoughts differ.

Heller-Nicholas, an Australian film critic and writer, creates a fascinating connection between Hooper’s sunbaked tale of a cannibal family with desert-set Aussie horrors like Wake in Fright and Wolf Creek. Meanwhile, Kusama sees the story as profoundly, almost poignantly American.

And Miike, genre master responsible for some of the most magnificent and difficult films horror has to offer, including Ichi the Killer and Audition, credits The Texas Chain Saw Massacre with inspiring him to become a filmmaker. And all because a Charlie Chaplin retrospective was sold out!

Philippe’s approach is that of a fan and an investigator. When Oswalt compares Hooper scenes to those from silent horror classics, Philippe split screens the images for our consideration. When Kusama digs into the importance of the color red, Chain Reactions shows us. We feel the macabre comedy, the verité horror, the beauty and the grotesque.

It’s fascinating what the different speakers have in common. So many talk about Leatherface, worry about him, pointing out that from Leatherface’s perspective, TCM is a home invasion movie.

What you can’t escape is the film’s influence and its craft. The set design should be studied. Hooper’s use of color, his preoccupation with the sun and the moon, the way he juxtaposes images of genuine beauty with the grimmest sights imaginable.

Each of these artists came to the film from a different perspective—some having seen it early enough in their youth to have been left scarred, others having taken it in as adults and still being left scarred. But each one sees layers and importance—poetry, even—in Hooper’s slice of savage cinema.

Chain Reactions is an absolute treasure of a film for fans of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.