Dolly

by Hope Madden

Fans of Savage Seventies Cinema, rejoice. Filmmaker Rod Blackhurst channels The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Tourist Trap, and even a little bit of Ted Post’s 1973 freak show The Baby for his wooded horror, Dolly.

Macy (Fabianne Therese) and Chase (Seann William Scott) hike through the woods to a breathtaking overlook where Chase will pop the question. But they probably should have turned back at the first sign of those baby dolls nailed to the trees.

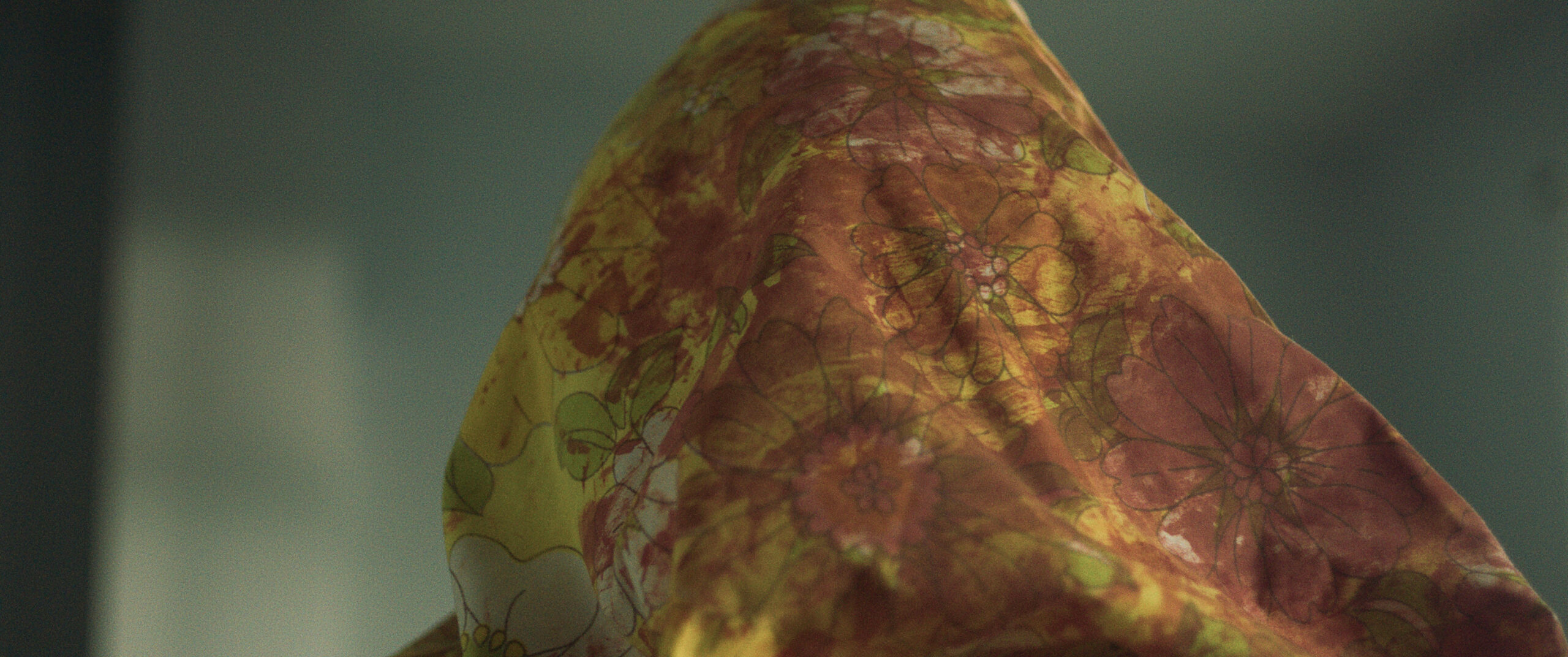

Soon enough, they meet Dolly (Max the Impaler, that’s quite a name), an enormous person whose whole noggin is hidden inside a cracked ceramic doll’s head. Dolly has a shovel, puts it to unusual use, and soon enough it’s just Dolly and her new baby, Macy, back at Dolly’s house.

Blackhurst nails the look and vibe of a 70s grindhouse horror show. And it’s not just tone, it’s also the content. Dolly gets nasty. Blackhurst intends to horrify you far more than frighten you. Whether it’s blood or body fluids or rancid food stuffs or broken bones that trip your gag reflex, he’s aiming to find it.

Ethan Suplee—you remember, the happy singing football player from Remember the Titans–cuts a far more intimidating presence as Daddy, and you can’t help but wonder about the backstory here at Dolly’s place. Kudos to Blackhurst, who co-writes with Brandon Weavil, for keeping it ambiguous.

Yes, if it’s an indie Seventies horror aesthetic you’re after, and logic and common sense are of less importance, then Dolly is for you. But if you crave one single scene of realistic behavior, the movie comes up short.

Therese can’t be blamed. She does what she can, her attempts at carving a heroic character are in and of themselves heroic. But Macy’s every action is made exclusively to further the plot and never, ever to create a believable character. If you have a tough time watching a person constantly abandoning weapons along with common sense, this film will frustrate you.

The excellent grindhouse violence and style are only equaled by the utter and distressing ridiculousness of the plot. So, even Steven, I guess.