We’re Not Safe Here

by Hope Madden

The nightmarish images and unsettling sound design of writer/director Solomon Gray’s We’re Not Safe Here more than make up for its narrative stumbles.

A lot of films open on a scene of horror to be contextualized later in the movie. Likewise, Solomon sets the stage early with a swift, troubling little gem of a horror show. But interestingly, the tale he builds around it taps into a terror more subconscious and dreamlike than what you might expect.

Sharmita Bhattacharya is Neeta, a schoolteacher by day/artist by night who’s been unable to get started on her latest painting. Frustrated at the easel one night, she’s surprised by a visit from Rachel (Hayley McFarland), another teacher who’s been missing. Frantic and increasingly panicked, Rachel spills a story that began in her childhood. Something she thought she’d lost has found her again.

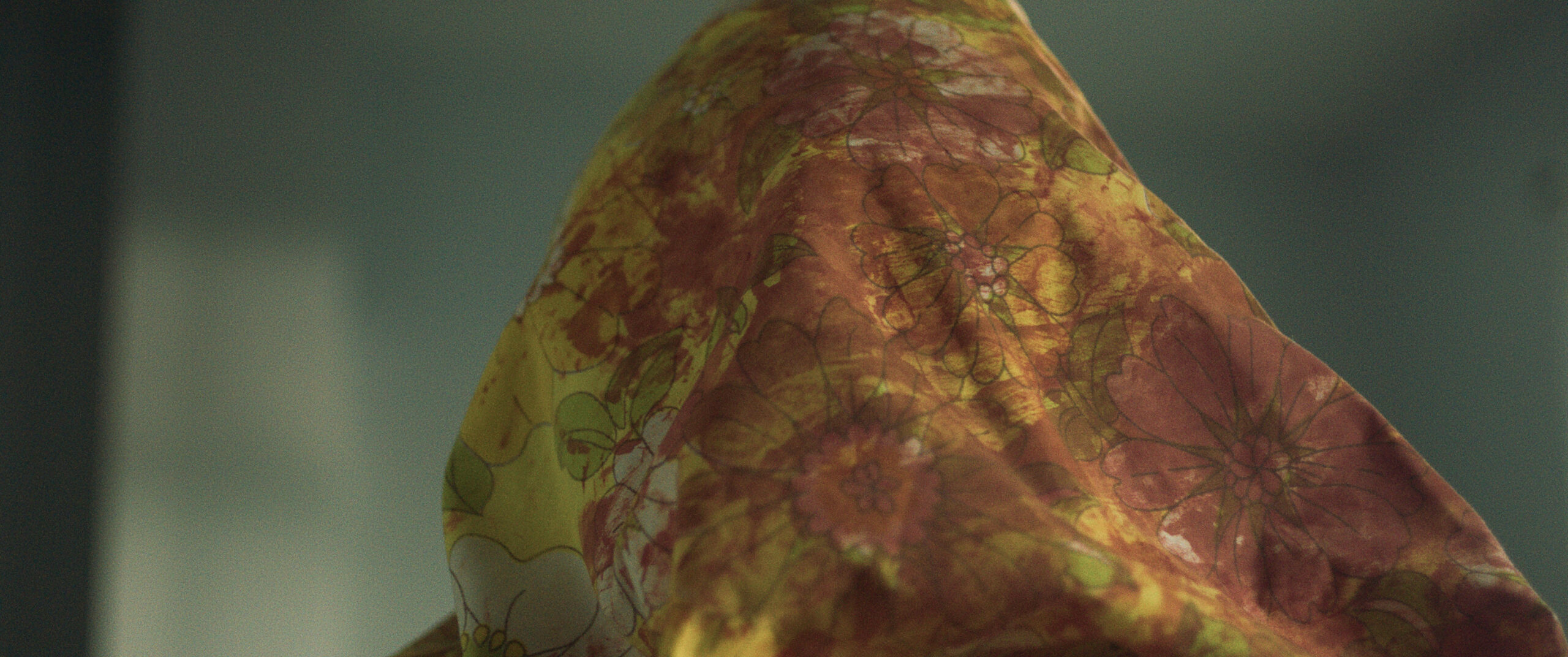

Aside from some very intimidating figures wearing bloody pillowcases over their heads (creepy!), We’re Not Safe Here is primarily a two-person show. McFarland is masterful, her paranoid madness tipped with a teacher’s command of the room. She’s mesmerizing.

Bhattacharya struggles a bit. Neeta is also troubled, and the performance feels stiff and unsure until the character gives into her demons. But there are moments between the two of them that are deeply upsetting. I mean that in a good way.

Gray’s use of setting—Neeta’s home, every wall cluttered with her sketches and paintings, every surface littered with books—creates a busy, fascinating space rich with potentially spookiness. A meandering camera and effective sound design capitalizes on what the set design has crafted: a lovingly lived-in space turned suddenly suspicious. The filmmaker evokes a kind of paranoia that feeds the perfect atmosphere for his film.

There’s a looseness to the script that often serves the film’s maniacal undercurrent. What’s delusion? What’s really happening? And is it contagious?

Gray refuses to fit all the pieces together, a choice that mostly pays off. The act structure and finale are rigid enough to give the tale a feel of completion. While a lingering vagueness in the backstory is frustrating, it also allows the imagination to veer into its own halls of madness.