Remember This

by Hope Madden

“What can we do that we are not already doing? Do we have a duty, a responsibility as individuals, to do something? Anything? And how do we know what to do?”

These words from Jan Karski, reluctant World War II hero and Holocaust witness, transcend the specific horrors Karski struggled with. They mean as much today as they did decades ago, and that’s just one reason Derek Goldman and Jeff Hutchens’s film Remember This strikes such a chord.

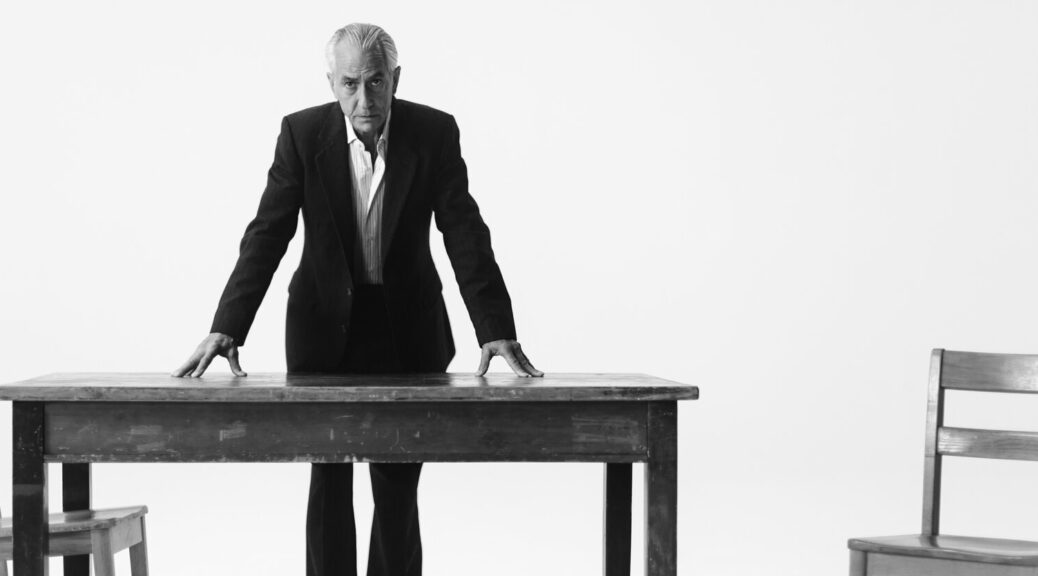

The other reason is David Strathairn. In a stirring performance, Strathairn brings Karski to life and he does it essentially on his own. Remember This is a one-man-show, a filmed stage play written by Goldman and colleague Clark Young, but co-directed by longtime cinematographer Hutchens (who also serves as DP). The combination brings a cinematic quality to the intimacy of the stage. But again, all of this is just support work, helping Strathairn compel your undivided, often teary attention for the full runtime.

The writing here is crisp and urgent and Strathairn delivers it beautifully. There’s nothing showy in his performance, and the unassuming delivery often lands harder than it would have with more drama.

Remembering attending mass and doing as his mother told him as a boy, “I was a good boy.” Recalling his pride to serve Poland and his befuddlement at the blitzkrieg: “Poland lost the war in 20 minutes.”

The poignant understatement serves an important purpose, because there’s no hint of exaggeration or drama or self-indulgence as the actor shares Karski’s recollections of the war, of the death camp, of his inability to persuade the leaders of the Allied forces that their immediate intervention was the only thing standing between Polish Jews and complete annihilation.

“Governments have no soul.”

Hutchens’s camera is subtle but its fluidity in orchestration with lighting, Roc Lee’s sound design, and Strathairn’s movement keep the film from ever feeling stagnant or stage bound. The final result is surprisingly unsentimental, Lee’s subtle score never overwhelming the delicate performance.

Strathairn talks, a broken figure filmed in stark, lovely black and white, and we learn what apathy and inaction can cause. It’s a heartbreaking lesson worth remembering.

“My faith tells me that the second original sin has been committed by humanity through commission or omission or self-imposed ignorance or insensitivity, self-interest, hypocrisy, heartless rationalization, or outright denial. This sin will haunt humanity to the end of time. It haunts me now. And I want it to be so.”