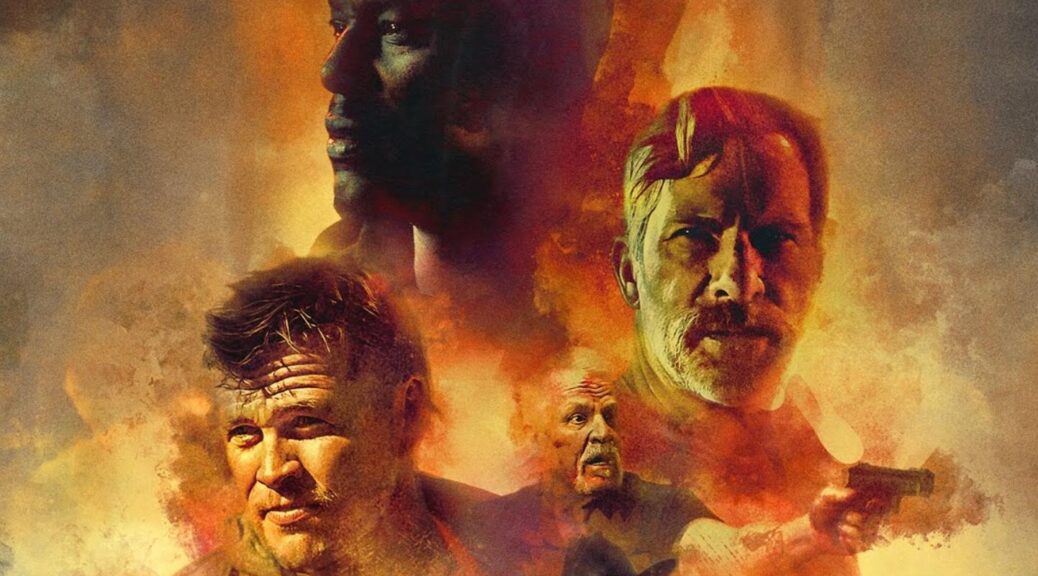

Marmalade

by Christie Robb

Newbie prisoner, Baron (Joe Keery, Stranger Things), needs to be back on the street by three p.m. Luckily, his new cellmate is a veteran at all things illegal, including successful jail breaks. And he’s bored. If Baron can spin a compelling enough yarn about why he needs to make his three o’clock meeting, Otis (Aldis Hodge, Black Adam) will get him there on time.

Veteran character actor Keir O’Donnell takes the helm to write/direct his first feature with Marmalade. And his casting is pretty great. Keery’s Baron shares a lot of the qualities that made his Steve from Stranger Things so much fun—great hair, the charisma of a golden retriever puppy, and a relentless devotion to his loved ones.

Here, Keery’s the caregiver of a bedridden mamma whose prescription medication just jumped up in price. All seems bleak until Marmalade (Camila Morrone, Daisy Jones and the Six) rolls into town. She’s got the pink hair, tattoos, and unconventional fashion sense of a manic pixie dream girl. But she’s also got a gun and a plan to rob a bank, so more a noir femme fatale who shops at vintage stores.

Marmalade is a little bit Forrest Gump and a little bit Natural Born Killers and a lot bit of another movie that I won’t mention because…spoilers. But you’ll figure it out before the credits roll.

It’s a stylish movie with good chemistry between cast members and some fun twists. However, the script deserved another few drafts before filming. In order to pull off what the film is trying to do, you need a tightly woven script that works the first time without giving away the ending, and that holds up to multiple viewings once you know. Here, there were plot holes as big as those in the hot pink fishnet tights that Marmalade so often wears.

But if you don’t mind that, Marmalade is pretty sweet.