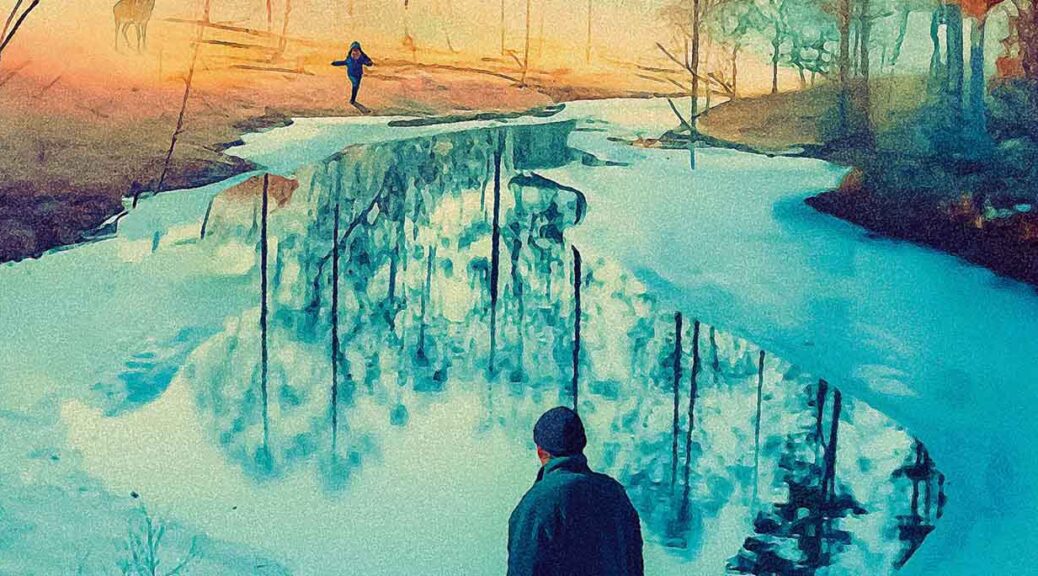

The Strangers: Chapter 1

by Hope Madden

Reny Harlin’s best film is The Long Kiss Goodnight, though some would argue Die Hard 2. Niether one of these is great. Good, yes. Definitely. Not great.

He’s made 42 other features—42!—not one of which is good. A couple are decent. A lot of people think he disappeared, talk about his work with The Strangers origin story trilogy as some kind of grand reemergence, but he’s never gone away. It’s just that the movies he’s made for the last thirtyish years have been entirely forgettable.

So anyway, The Strangers: Chapter 1.

Chapter 1 is actually the third installment in the tale of masked marauders randomly hunting anybody who’s home when they come calling. Bryan Bertino’s 2008 original is among the scariest horror films of the new millennium. It took ten years for somebody to decide it needed a sequel. It didn’t.

But that’s the problem with a franchise, isn’t it? You can’t replicate the genuine terror of a truly original horror film, you can only hope to replicate it. This is what Harlin, with writing partners Alan R. Coen and Alan Freedland—both comedy writers known for King of the Hill and other sitcoms—attempts. Chapter 1 hits all the same beats—all of them—as Bertino’s original. The only real difference is that he abandons every move that made the original original.

Gone is the complicated relationship, emotional gut punches, chilling lines and good music. The vinyl collection in this backwoods Airbnb is terrible.

Maya (Madelaine Petsch) and Ryan (Froy Gutierrez) stop at an off-the-grid diner on their road trip from NYC to Portland, Oregon. Unexpected car trouble lands them in a rustic cabin overnight, which seems ideal until someone comes knocking looking for Tamara.

There’s a Richard Brake sighting, which is never a bad thing, but blink and you’ll miss him. Gutierrez and Petsch are fine. They’re asked more to pose and look nice than anything, but they do emit a lovable chemistry that makes you sorry for what you know is in store.

And though you certainly know where things are heading (partly because Harlin mimics Bertino’s original so early and often), individual set pieces ratchet up a certain amount of tension. It looks nice. Is it the gorgeous vintage horror aesthetic of Bertino’s original? It is not. But it’s a good looking movie.

So, if you have not seen the 2008 treasure that grounds this franchise, then Harlin’s Chapter 1 is sure to please. It’s an extremely conventional, competent horror movie. As if that’s enough.