Evil Does Not Exist

by George Wolf

Two years ago, the magnificent Drive My Car became the first Japanese film to garner a Best Picture Oscar nomination, and earned Ryûsuke Hamaguchi well-earned noms for writing and directing.

Now, writer/director Hamaguchi rewards his wider audience with Evil Does Not Exist (Aku wa sonzai shinai), another thoughtful, gracefully intellectual tale that finds him in an even more enigmatic mood.

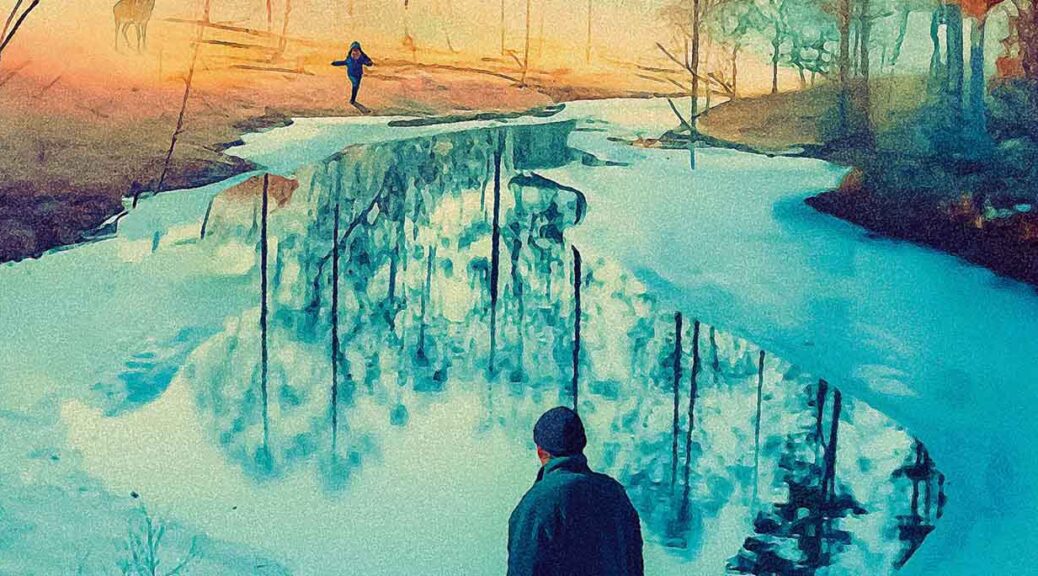

Takumi and his young daughter live in Mizubiki, a Japanese village near Tokyo. Father teaches daughter about the wonders of nature, and about her place in the village’s careful balance of give and take.

That balance is threatened when a big firm plans to build a ”glamping” (glamorous camping) site very close to Takumi’s own house. Two P.R. reps come to convince the villagers that the company will also be careful, but these townsfolk know manure when they smell it.

The reps try to curry favor by offering Takumi a job as caretaker of the glamping site, but the more time they spend with this pillar of the simple life, the more they start to see wisdom in his ways.

Hamaguchi delivers some salient points on ecology while showcasing his skill with probing character purpose, motivation and the different ways they interact.

At a town meeting, an older villager gently reminds the P.R. reps about the responsibilities that come with “living upstream,” and the speech becomes an eloquent metaphor that the film begins dissecting with sometimes abstract detail.

And though the one hundred six-minute running time might seem rushed for a filmmaker that has favored three, four, and even five-hour films, Hamaguchi’s storytelling here is more patient than ever. Yoshio Kitagawa’s exquisite cinematography often showcases nature’s beauty in wordless wonder, always buoyed by an Eiko Ishibashi score that is evocative and moving.

What Evil Does Not Exist doesn’t do is provide any easy answers for the dramatic choices Takumi makes once his daughter goes missing. The film ends as it begins, staring into the natural world and asking us to ponder how we best fit in.