Air Doll

by Hope Madden

There has always been something creepy, narcissistic and sad about the story of Pygmalion and Galatea. In the hands of Hirokazu Koreeda (Shoplifters), it becomes a soft-spoken, melancholic tale of modern isolation.

As delicate a film as Koreeda has made, his 2009 Japanese fantasy based on Yoshiie Goda’s manga shadows a sex doll who awakens to an unsuspecting — and mainly disinterested – world.

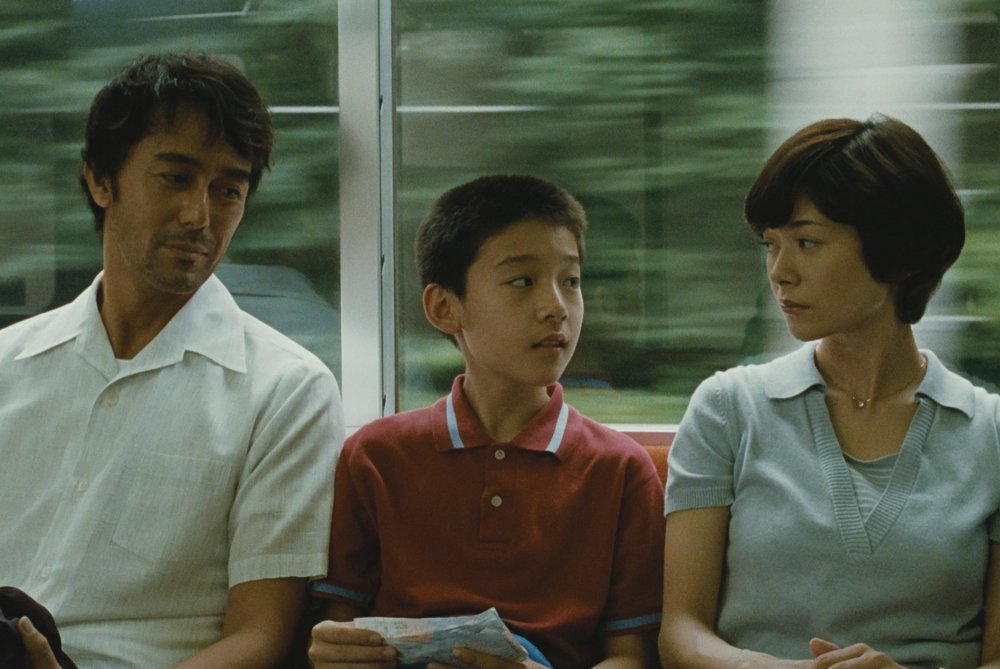

Disgruntled waiter Hideo (Itsuji Itao) can’t wait to come home from work every night to his waiting, patient, perfect girlfriend Nozomi. She listens, never says or does anything annoying, asks for nothing and is up for anything.

Nozomi (Bae Doona, Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance) is a sex doll, and after one perfectly ordinary night of servicing Hideo, Nozomi wakes up. While Hideo is at work all day, Nozomi explores the world and learns to be human.

This story could go sideways quickly. On the surface, the tale reads as cloying, sentimental and potentially unendurable— like Mannequin, with an emptiable chamber between its legs.

And yet, Koreeda’s wistful film escapes all of that. Doona’s delicate performance brings heartbreaking tenderness to the existential dread underlying the story. Nozomi aches for answers, for a purpose. Here the film tests the same waters as many, from Blade Runner to A.I. to Toy Story.

But Nozomi’s story is decidedly female. Pygmalion didn’t want a human being, he didn’t want another messy, needful thing. He wanted Galatea precisely because she wasn’t a human woman. The moment of revelation that humanity is a woman’s greatest fault is as quietly devastating as the rest of Air Doll’s running time combined.

Periodically, Koreeda’s camera veers through the lives of a handful of tangentially related souls, each more crushed by loneliness than the last. These montages tweak the film’s tone, set it in a slightly different, more foreboding direction.

Hirokazu Koreeda made Air Doll in 2009, but it’s never gotten a US release. It hits American theaters and streamers Friday. Don’t wait for Valentine’s Day to watch it, trust me on that one, but watch it nonetheless.