Lie With Me

By Rachel Willis

Past memories and present regrets mix in director Olivier Peyon’s film, Lie with Me.

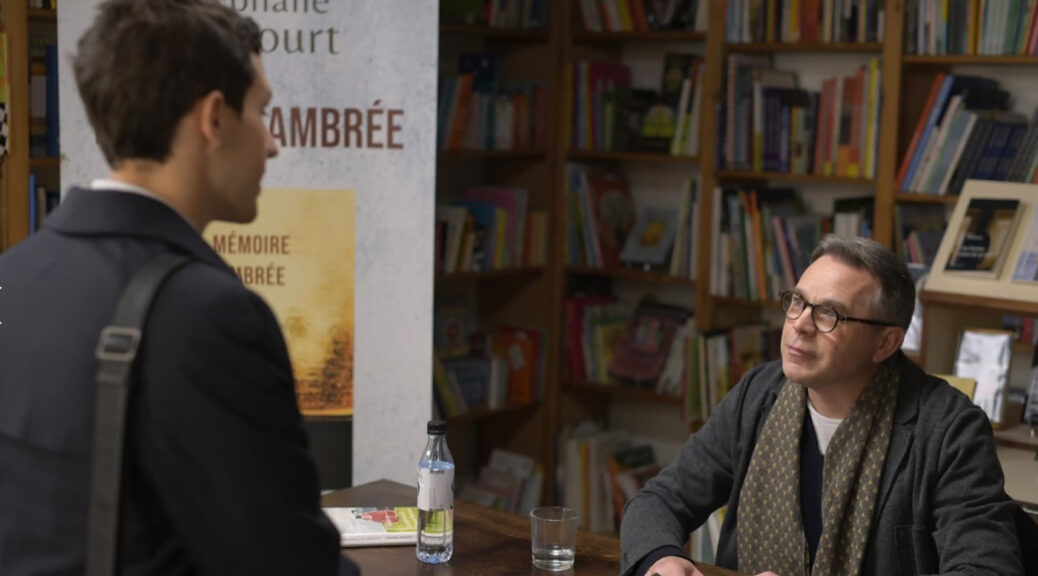

Returning to his hometown after decades away, celebrated author Stéphane Belcourt (Guillaume de Tonquédec) looks to dig up the ghosts of his past in hopes of inspiring something lost. Or in this case, one ghost.

In 1984, a young Stéphane (Jérémy Gillet) begins a relationship with popular student, Thomas (Julien De Saint Jean). The only condition of their relationship is that no one can know. What starts as something tawdry deepens as the two boys spend more time together. Scenes from the past intermingle with scenes from the present, as memories of his first love overwhelm an older Stéphane.

It’s not clear if Stephane expects to encounter his past love when he returns, but he is floored when instead he meets Thomas’s son, Lucas (Victor Belmondo).

There are two very touching relationships in the film as we watch the budding romance between Stéphane and Thomas unfold, along with Stéphane’s friendship with Lucas. The two actors portraying Stéphane are equally skilled at bringing the character to life in a seamless blend of one person at two different times in life. It’s as effectives as the contrasting natures of Thomas and his son, Lucas. Where Thomas is reserved, never revealing who he is, Lucas is at ease with himself.

The slow steps the film takes in trying to reveal Thomas are elusive; can we ever really know a person who doesn’t know himself? In hiding a part of himself from everyone but Stéphane, he essentially lives a stunted life.

There are some scenes that don’t always work. A few are too heavy-handed and sentimental in a film that works better when it embraces restraint. As the older Stéphane, de Tonquédec can convey a range of emotion with his expressions. When his controlled façade slips, we see sadness and radiance as he recalls moments of love and loss.

The movie isn’t perfect, but it’s touching. There is a quiet sadness that haunts Stéphane as we follow him through his memories. While some scenes carrying a heavy weight, the film is not without hope. While it’s true there are some people we can never really know, often they leave hints, revealing as much of themselves as they can. It’s depressing, but it’s hopeful, too.

Perhaps one day, the world will learn the accept others for who they are and there will no longer be a need to hide.