Just the Two of Us

by Eva Fraser

L’amour et les Forêts. Love and the Forests. This title, in the film’s original language, deepens the meaning of the English title “just the two of us,” encompassing the audience in a tale of love so vast, manipulative, and obsessive it becomes suffocating like the sickly sweet air in a watchful forest.

Just the Two of Us, directed by Valérie Donzelli, is a story we’ve seen before. That lessens nothing. These 105 minutes of lust, fear, and desperation center on Blanche Renard (Virginie Efira) and her relationship with Grégoire Lamoreux (Melvil Poupaud)— documenting its toxic development over nearly a decade.

As soon as the film begins, cinematographer Laurant Tangy gives it life with his close-up shots of micro-movements and facial expressions that tell all. The lighting strengthens every shot, intensifying the emotions of each moment: red for lust, blue for a calculated almost-love, and green for jealousy. Everything teems with vibrancy, then it doesn’t, signaling that something must be wrong, priming us for a closer look.

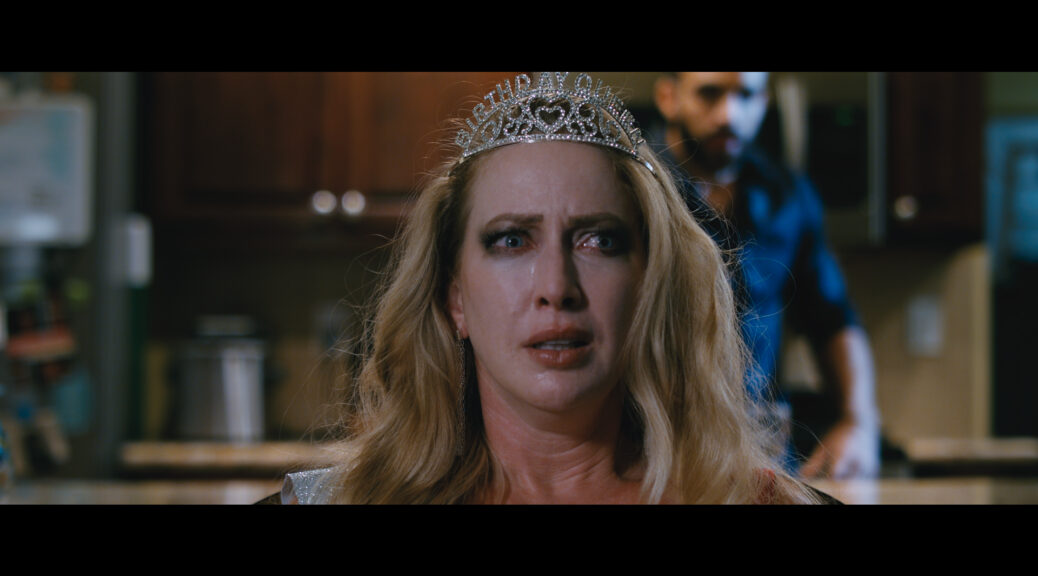

The performances in this film are phenomenal. Efira, who plays twin sisters Blanche and Rose, conveys everything with her deep, expressive eyes. At one point, she licks a tear from her own face so quickly it seems invisible.

Poupaud terrifies as Grégoire, his sharp-witted duality between tenderness and cruelty giving the film its rightful label as thriller. There are no fantastical monsters or jump scares, only the dramatic irony of a dangerous relationship.

Time feels ambiguous and the pacing variable, but it works with the concept of a disorienting relationship that puts love in a liminal space. A few loose ends don’t taint the film because its main focus is the relationship, not the minute details.

Be warned: this film is very intense and could be triggering for those who’ve been in an abusive situation. Just the Two of Us is beautiful with its realism, but it is also hard to watch. But the stunning performances and technical execution are worth it.