Ghost Train

by Rachel Willis

Several strange incidents at a subway station spark the curiosity of a YouTube content creator in director Se-woong Tak’s film Ghost Train.

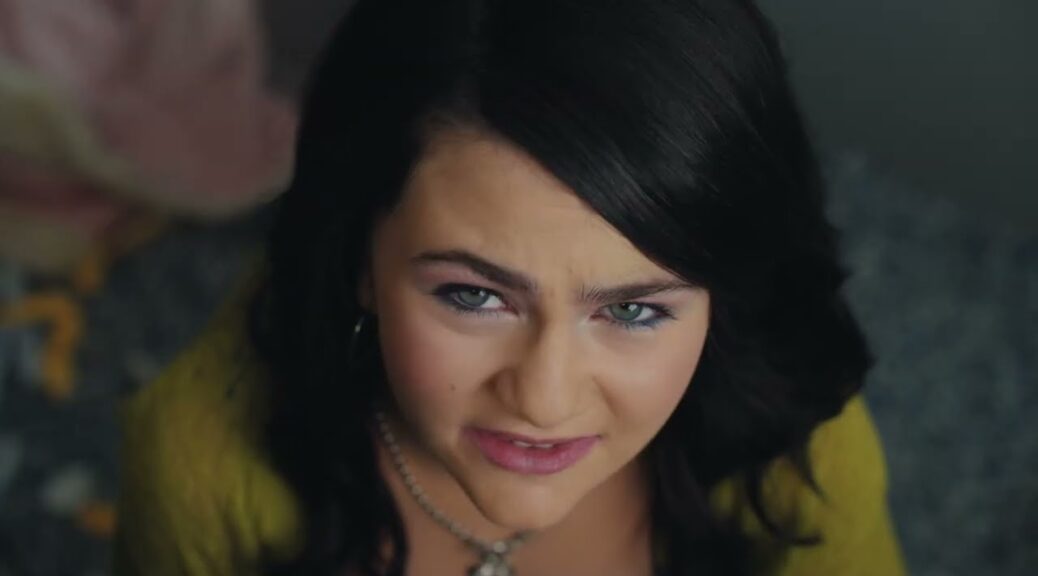

To understand the real issues surrounding the rash of bizarre occurrences, Horror Queen Da-kyeong (Joo Hyun-young) bribes tales from a station master (Jeon Bae-soo) with fancy spirits (some of which I wouldn’t mind trying).

As the station master spins each yarn, we’re privy to what really happens to each person at the center of the individual tales. At times, what we’re shown during the movie is not what appears on the surveillance tapes the station master shows to Da-kyeong.

There are several unsettling concepts at work to help unnerve the viewer. A woman who repetitively bangs her head against the train door sends passengers scurrying to another car. This is a motif that pops up at different moments, helping to create an atmosphere of dread.

Each of the station master’s stories has a uniqueness that makes the movie flow like an anthology horror. However, the style and atmosphere remain consistent, setting a creepy tone throughout.

The framing story is the movie’s weak link. The Horror Queen herself isn’t nearly as compelling as the individuals in the station master’s tales. Da-kyeong’s nemesis at work is a stereotypical mean girl, and her work love interest is about as interesting as a blank sheet of paper. It’s with impatience that we wait for the next of the station master’s tales.

However, as the film enters the final act, the framing story picks up steam. As Da-kyeong learns more about the station and its history, her story starts to get its teeth.

Unfortunately, those teeth are never quite sharp enough to explain the overall mystery around the ghost train. While there are a lot of memorable and interesting parts, they never quite come together as single narrative. That said, the movie is creepy enough to remain interesting, and overall, an intriguing series of ghost stories.